1503: Frenchman’s Gully Rock Art

November 21, 2022

By AHNZ

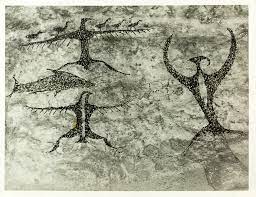

There are hundreds of pre-Maori rock art sites in South Canterbury, including some very special ones at Frenchman’s Gully at Pareora Gorge near Timaru. Here we see some of the few (only) pictures of the long extinct moa. No Maori ever saw a moa. The giant bird was the primary resource of an earlier culture and they’re the ones who created these ‘painted’ caves. The Freenchman’s pictures are also special for being outline drawings when almost all others are filled-in silhouettes.

There are hundreds of pre-Maori rock art sites in South Canterbury, including some very special ones at Frenchman’s Gully at Pareora Gorge near Timaru. Here we see some of the few (only) pictures of the long extinct moa. No Maori ever saw a moa. The giant bird was the primary resource of an earlier culture and they’re the ones who created these ‘painted’ caves. The Freenchman’s pictures are also special for being outline drawings when almost all others are filled-in silhouettes.

The Frenchman’s Gully pictures (image, left) were discovered by Settlers (son of Mr Evans) in about the 1860s. We see a fish, an eagle, and a couple of tailed ‘birdmen’ with ‘chicks’ running along their arms. The birdman’s head is in profile but the body and tail suggest a perspective of looking down upon prey as a Moa Hunter might. The have been drawn in charcoal and, probably, animal (moa) fat.

“…and cave drawings at Pareora, in South Canterbury, including three of the four known drawings of moas in Maori rock art.” – Need Seen To Preserve Prehistoric Maori Sites, Press (1965,) Papers Past

“The entire surface of the rock is covered with drawings, which, however, are unfortunately so defaced by modern scrawls, that it is impossible to distinguish their exact forms. For since the natives have lost their superstitious regard for these relics of antiquity, the eeling parties who frequent the spot make a practice of scratching rude drawings with charcoal all over them.” – James Stack, Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, South Canterbury NZGenWeb Project, Rootsweb

“Mr Hugh Simms McCully..has the original tracings of a rock drawing on Pareora limestone discovered by a son of Mr Ben Evans, of Pareora Gorge….there is little doubt that one drawing is of moa-hunter date, and may even throw light on how the moa was taken.” – ROCK DRAWINGS LINKED WITH MOA-HUNTER AGE, Press (1958,) Papers Past

When James Stack visited this, or nearby, rock art sites in 1875 he found them already much defaced, drawn over, and faded. A girl named Alice wrote to the Otago Witness (1911) of her Sunday School Picnic to Frenchman’s Gully describing “I went to a cave, and in the cave were painted craatures which I don’t know about.” Nearby, Alice also saw a rock resembling a man’s face. Another girl, Audrey Gibson, wrote to the Timaru Herald (1930) to say, “One day we went to Frenchman’s Gully. In a cave we saw Maori paintings, such as—a fish, a shield, a lizard, and many other curious things.”

When James Stack visited this, or nearby, rock art sites in 1875 he found them already much defaced, drawn over, and faded. A girl named Alice wrote to the Otago Witness (1911) of her Sunday School Picnic to Frenchman’s Gully describing “I went to a cave, and in the cave were painted craatures which I don’t know about.” Nearby, Alice also saw a rock resembling a man’s face. Another girl, Audrey Gibson, wrote to the Timaru Herald (1930) to say, “One day we went to Frenchman’s Gully. In a cave we saw Maori paintings, such as—a fish, a shield, a lizard, and many other curious things.”

Unfortunately I don’t yet have a picture of the 3 moa at Frenchman’s to share. A copy was once an essential part of Canterbury Museum’s pre-Maori exhibition, now long-gone. Duff teamed up in 1946 with Theo Schoon to preserve Canterbury rock art and helped him get State funding to carry on this work by sketching and painting what they found. One of these moas gave Duff some interesting ideas as we shall see.

“The Maori people Claimed neither first hand or traditional knowledge of the artists” – MAORI

ROCK DRAWING – The Theo Schoon Interpretations, Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch Art Gallery“Most drawings are monochrome, either black silhouette or outline images, however, imagery with blank centres does occur as at Frenchmans Gully..” – ibid

During my visit to the recent Canterbury A&P Show (2022) I visited the Heritage New Zealand stand which had dedicated itself to Canterbury Rock Art. The women manning the stand passed me between one another up the ranks until someone could answer my question about rock art. Expensive-looking pannels framed the stand and I wanted to know HNZ’s interpretation of what they were showing we thousands of visitors. Unfortunately they had no knowledge to offer at all! Instead they kept trying to offer me chocolate and get me to take a ‘heritage’ quiz that doubtless would wind up with me handing over my name and contact details to their database in return for some arbitrary heritage score…no thanks.

During my visit to the recent Canterbury A&P Show (2022) I visited the Heritage New Zealand stand which had dedicated itself to Canterbury Rock Art. The women manning the stand passed me between one another up the ranks until someone could answer my question about rock art. Expensive-looking pannels framed the stand and I wanted to know HNZ’s interpretation of what they were showing we thousands of visitors. Unfortunately they had no knowledge to offer at all! Instead they kept trying to offer me chocolate and get me to take a ‘heritage’ quiz that doubtless would wind up with me handing over my name and contact details to their database in return for some arbitrary heritage score…no thanks.

The best the chocolate-distributing archeologist woman could offer was that to know what the rock art means you must consult the official Maoris. She said they had oral traditions going back to the time the drawings were made and held tight to that opinion despite my expressed scepticism. Insisting the drawings were figurative and in no way narrative “because taniwhas don’t exist,” she reaffirmed that only the official Maori rock art authority in South Canterbury could interpret these drawings. I wondered, as I left, with my free HNZ sticker, why the Maoris were not the ones at the A&P Show then and not HNZ?

The burning question I had was about Roger Duff’s interpretation of one of the Frenchman’s Gully moas. Duff told visitors from the New Zealand Archaelogical Association Conference of the early 1950s that one of the pictures showed a moa with a special forraging adaptation to its foot. With 3 toes on one foot and 7 toes on the other this was the “rake-footed moa.” I couldn’t see that picture (image, right) at the HNZ wall.

Duff’s assertion was challanged that day by a member of the Conference party, Trevor Hosking. I put his idea to the HNZ chocolate-weilding archeologist but she could only regress back to absent Maori experts in figurative interpretation. “It seemed clear to me that I was looking not as a rake footed moa but a moa trap operated by a hunter. Moa had regular trails or ‘moa roads.’ Early settlers were at first mystified by the well worn trails travelling across country in straight lines. The trap was set up on the track and the moa scared into running down it. The rope was tightened and the tines of the trap lifted off the ground. The moa’s foot became wedged and down the bird went…If a foot was entangled, a hunter could approach safely with a club or a spear…The line from the ‘rake’ to the man indicated to me that the artist drew himself trapping a moa. My observation did not please the academics in attendance. Dr Duff was especially disgruntled as the group could easily see what I was on about when the drawing was closely examined.” Ref. Harrington (2007)

Duff’s assertion was challanged that day by a member of the Conference party, Trevor Hosking. I put his idea to the HNZ chocolate-weilding archeologist but she could only regress back to absent Maori experts in figurative interpretation. “It seemed clear to me that I was looking not as a rake footed moa but a moa trap operated by a hunter. Moa had regular trails or ‘moa roads.’ Early settlers were at first mystified by the well worn trails travelling across country in straight lines. The trap was set up on the track and the moa scared into running down it. The rope was tightened and the tines of the trap lifted off the ground. The moa’s foot became wedged and down the bird went…If a foot was entangled, a hunter could approach safely with a club or a spear…The line from the ‘rake’ to the man indicated to me that the artist drew himself trapping a moa. My observation did not please the academics in attendance. Dr Duff was especially disgruntled as the group could easily see what I was on about when the drawing was closely examined.” Ref. Harrington (2007)

Hosking, perhaps New Zealand’s greatest ameteur archeologist, has an amazing hypothesis here worth checking out. It seems to have made accademics in the 1950s as uneasy as it did when I repeated it myself to one in 2022. The moa-hunting interpretation would make for fantastic narrative meaning to the rock art, essentially a schematical drawing similar to the hunting scenes in European cave paintings.

“…for example in the “bird-man” the head is viewed in profile but the body and tail appear as if seen from above. Sometimes a blank area of stone is left in the centre of a design to form a contrast with the filled parts. This blank central area can be seen in the lower “birdman” at Frenchman’s Gully.” – p217, New Zealand’s Heritage (1973)

“The Waitaha were driven into back country of the Lake District where their rock drawings remain.” – 1500: The Waitaha, AHNZ

“Canterbury Museum curators are thus priming your brain to regard the object as Maori. The truth is they have no idea.” – 1501: Waitaha’s Lost Luggage?, AHNZ

“Te Manunui provides outstanding evidence of traditions and practices of Maori occupation…” – Te Manunui Rock Art Site, Heritage New Zealand

New Zealand history has revised Moa Hunter culture right out of the books, almostly completely. Everything is just ‘Maori’ now, obliterating the cultures who came before the Maoris. It is therefore Politically Incorrect to share the cave art of the moas and all the more so if Hosking’s point were to be valid. Because there is a fear he may have been right the question must not be raised. To think about what this art might show would be to contradict the Maoris Always narrative.

Maoris never were the ‘tangata whenua’ but history has been re-written so that they are. It’s also interesting to consider that our modern roads did not at all start out as Maori tracks. The start was with the tangata whenua pathways that the Maoris simply colonised just as the Settlers after them would too.

It is true that early interpretations, from Stack on down to Duff, thought the cave pictures were idle “scribbles.” Figurative, rather than narrative as Hosking suggested. After thinkers such as James Frazer turned that idea on its head it became possible to think of the pictures as practical magic. They were functional, not just Stone Age graffitti to pass the time while the moa ovens baked your dinner. We don’t have to go along unquestioningly with Heritage New Zealand’s fawning over the Ngai Tahu Maori Rock Art Trust that these are figurative pictures that mean what they say they mean. According to Frazer (and even modern motivators like Tony Robbins,) by visualising and pre-figuring your success with drawings you are gold-setting and summoning desired ends. We know this as psychology but to the pre-Maori this was magic; It’s the same thing.

It’s unfortunate New Zealand is deprived of a bit of prehistory that was, only a couple of generations ago, in pride of place in our museums. Now, it’s unthinkable.

—

Ref. A Museum Underfoot, The Life Story of Trevor Hosking, Alison Harrington (2007)

Ref. Otago Witness, Papers Past

Ref. Timaru Herald, Papers Past

Image ref. ‘Rake-footed moa’, Theo Schoon, Canterbury Museum, Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share