1918: The Storming of King Edward Barracks

April 29, 2020

By AHNZ

Today in New Zealand history, 29 April, 1918, Christchurch was in an uproar. In the thick of World War One, our State had activated the Second Division lottery ballot. Conscription to fight the Great Wrong War was now applied to married men. Division One had applied to the unmarried or recently married, the childless, widowers etc. but that source of fresh meat had now been used up. Today in history the men whose name had come up were required by The State to present themselves for service.

Today in New Zealand history, 29 April, 1918, Christchurch was in an uproar. In the thick of World War One, our State had activated the Second Division lottery ballot. Conscription to fight the Great Wrong War was now applied to married men. Division One had applied to the unmarried or recently married, the childless, widowers etc. but that source of fresh meat had now been used up. Today in history the men whose name had come up were required by The State to present themselves for service.

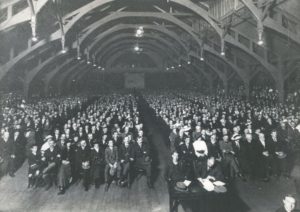

In response, some 5000 protesters, mainly women and children, mobbed King Edward Barracks where the registrations were to take place.

National Registration Act, 1915

Since 1915 New Zealand’s political rulers, the National Ministry, had quite un-democratically decided we were going to join The Great War. Massey and Ward, Reform and Liberals, merged their wings and worked together to ruin the nation rather than the usual theme of taking it in turns. They decided there would be no General Election until 6 months after the War ended (later adding on 1 year and 1 month because..they could.) Citizens and the Blindfold Parliament had little or no say in what the 12-man dictatorship did for their extended term. Two such Acts that the Minister of Defence, James Allen, soon put in place were the National Registration Act and the Military Service Act (1916) which forced New Zealanders into their army.

The Registration Act involved a ‘have you stopped beating your wife yet’ Impossible Situation mind trap. Each man between 19 and 45 was asked if they volunteered for Military Service OR were they willing to Serve otherwise? It was a Catch 22: Either answer was counted as a “volunteer.”

The Second Division League

Naturally, many New Zealanders were outraged at the unprecedented control The State was exerting over their liberty. The r-selected cultures, in particular, were bristling and fermenting. Impositions like the Government’s conscription and the Government’s Influenza Pandemic were ways to keep a difficult citizenry in line.

The Second Division League was formed by citizens as a reactive organisation to the Second Division muster. This anti-conscription lobby attracted thousands of civilly disobedient Kiwis. When Class B of the Second Division was called (13-17 April, 1918) they were mainstream enough, though frowned upon by the conservative social set and the Fourth Estate. The president of the Canterbury Second Division League, Maurice Gresson, belonged to a leading family of lawyers and judges¹. On Monday, April 28th, a “monster public meeting” of the League, over 1,600, was chaired by the Christchurch Mayor², Henry Holland. It was at this meeting that the League transitioned into radicalisation…

“Stand out!” men yelled. “Yes, stand out!” yelled women, taking up the cry. “Don’t go to camp!” – Eldred-Grigg

“..jumped to their feet and moved that ‘no Second Division man shall leave for camp until the demands of the League are acceded to.’ The audience went wild. ’Stand out! Stand out!’ yelled the audience, ‘Don’t go to camp!’

“The next day the city was electric as thousands of women, their babies and children in hand, gathered at King Edward Barracks to prevent the mobilisation.”- Archives NZ

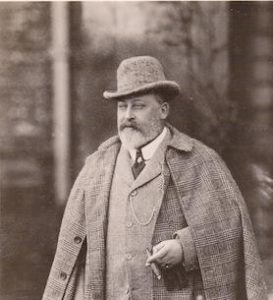

Perhaps Gresson and Holland were Controlled Opposition all along. At any rate, the League was too radical and estranged for both men now. Next morning, after the meeting, Gresson put out a press release resigning his position as president. Mayor Holland, father of future National 1.0 Prime Minister Sydney Holland (image right,) had raised fists directed at him and was hooted at by those storming King Edward Barracks next day. Holland lost the next mayoral election (1919) to his competitor, Henry Thacker, who, with James McCombs, had been a darling of the radicals of the League. By contrast, Holland had easily beaten the ‘end conscription’ campaign of McCombs on a platform of ‘Winning the war’ in the election prior.º

Perhaps Gresson and Holland were Controlled Opposition all along. At any rate, the League was too radical and estranged for both men now. Next morning, after the meeting, Gresson put out a press release resigning his position as president. Mayor Holland, father of future National 1.0 Prime Minister Sydney Holland (image right,) had raised fists directed at him and was hooted at by those storming King Edward Barracks next day. Holland lost the next mayoral election (1919) to his competitor, Henry Thacker, who, with James McCombs, had been a darling of the radicals of the League. By contrast, Holland had easily beaten the ‘end conscription’ campaign of McCombs on a platform of ‘Winning the war’ in the election prior.º

Christchurch’s moral temper had changed.

The Storming of King Edward Barracks

On Tuesday, 29 April, 1919, Second Division men were to report to the corner of Montreal Street and Cashel Street. Here there was a massive military hanger, the King Edward Barracks, est. 1905, named of course for our Sovereign at the time, King Edward. (This was the King said to live a “silly useless life” in his son’s New Zealand diary just 2 years later.)

On Tuesday, 29 April, 1919, Second Division men were to report to the corner of Montreal Street and Cashel Street. Here there was a massive military hanger, the King Edward Barracks, est. 1905, named of course for our Sovereign at the time, King Edward. (This was the King said to live a “silly useless life” in his son’s New Zealand diary just 2 years later.)

“..the city was electric as thousands of women, their babies and children in hand, gathered at King Edward Barracks to prevent the mobilisation.”- Archives NZ

Instead of an orderly scene, the Barracks were mobbed by some 5000 citizens who were mostly women who also brought along their children. At one point, a police arrest was reversed when 300 of the crowd leapt forth to de-arrest him. In the end none, or perhaps half depending on the source, of the men called up were able to be processed. The radical League had won the day.

The New Left

On the one hand we have these women fighting hard to resist the Great War or our role in it. By contrast we often hear of other women shaming and ‘white feathering’ men, calling them out publicly, to insist they enlist into the war. These are two separate classes of women, roughly speaking they are K vs r-selected in mentality and culture.

On the one hand we have these women fighting hard to resist the Great War or our role in it. By contrast we often hear of other women shaming and ‘white feathering’ men, calling them out publicly, to insist they enlist into the war. These are two separate classes of women, roughly speaking they are K vs r-selected in mentality and culture.

I have my doubts the League women or New Zealand-Irish MPs such as James McCombs & Henry Thacker, or Industrial Workers of the World were really against the war as a principle. Rather, they seem to be taking the opportunity to insert their own socialist agenda into the discourse and grow, for example, the Labour Party.

On the other side of the world Irish-Irishmen had been seizing a similar advantage for themselves while Britain faced The Great War by trying to take over Dublin in The Easter Rising. Neither of these Irish groups had any patience toward good political sportsmanship³.

McCombs, Thacker, Savage, Fraser, Semple, and others were good to go with WW1. They just wanted the burden to be upon the (wealthy) class they did not represent rather than the workers they did. Over the coming years they capitalised and rose to power.

“It is arguable that the beginnings of New Zealand’s ambivalent attitudes to business can be traced to this period.”; Goldsmith (2008)

Pounding pandemics and conscription upon a rising r-selected mainstream doesn’t keep them from coming, it just makes them more radical. When the 1919 election did finally come the new mainstream policy on offer from the Liberal faction, Ward, was basically the Communist Manifesto! The New Zealanders radicalised by their resistance to Great Wrong War set the bedrock for a particularly exotic and potent New Left that finally culminated in Labour 1.0.

—

1 Ref. p373 The Great Wrong War; Stevan Eldred-Grigg

2 Ref. Anti-conscription Protesters Storm King Edward Barracks,; Archives New Zealand; Flickr

º (citation update) “The 1917 mayoral election was contested by Holland and the MP James McCombs along the lines of win-the-war (Holland) and anti-conscription (McCombs). The result was a crushing defeat of McCombs” – Wiki

3 Not to mention the even greater comparative chaos under way in the Russian Revolution of the same time period

Image ref. 2,600 people rally against conscription and cost of living in Christchurch 1917. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, New Zealand; Garage Collective

Ref. 1933: Death of Harry Holland; AHNZ

Ref. Disenchantment with the New Left revolution followed; Before Riverside; AHNZ

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share