1842: The Raupo Houses Act

March 3, 2024

By AHNZ

Today in history, 3 March, 1842, self-declared Governor of New Zealand, William Hobson, passed the Raupo Houses Act.

Today in history, 3 March, 1842, self-declared Governor of New Zealand, William Hobson, passed the Raupo Houses Act.

This placed a huge £20 tax on anyone with a ‘Maori House’ within the boundaries of what The State defined as a town.

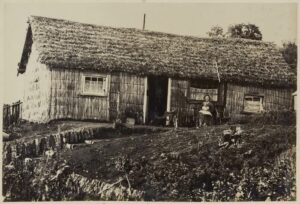

The Maori fiber house technology had been adopted and improved by the new colonists to impressive effect (see image, left.) In the North Island there was plenty of this wetland fiber to gather up for free. With some framing and a few hours of labour you could have yourself a house. Some of them were very impressive but none were built to last more than a few years. That was OK, they were a gate-way domicile for entry-level colonists to improve upon as they built their new life in New Zealand.

Outside towns it was still legal to build this way so the rule didn’t get in the way of pioneers or Maoris.

The burden of the legislation fell on the working class folk who were trying to establish themselves and earn themselves the the more substantial home they, of course, wanted.

According to Harman (2014) the law was given effect in Auckland on 16 May 1842, Wellington, 30 March 1843, and in Dunedin and Port Chalmers, On 28 January 1850.

So, the Government has been messing up our housing market from the very start. And, using it as a source of revenue gathering for itself in the guise of “safety.”

“With just a few days’ work a labouring man could cut enough raupo for a ‘good-sized cottage’, and raupo houses represented good value, costing settlers as little as £7 to £8 in the 1860s for a three-bedroom home.” – Daily Southern Cross, Harman (2014)

“Those structures that avoided incineration disintegrated after about half a decade’s use and were often seen by settlers as makeshifts to be replaced with timber, stone, or brick buildings as their finances improved. Therefore, raupo buildings did not become a permanent feature of colonial New Zealand’s built environment and were, from the outset, a benchmark against which the material prosperity, development, and growth of the colony could be measured as they faded from the scene.” – ibid

“…’every building constructed wholly or in part of raupo, nikau, toetoe, wiwi, kakaho, straw, or thatch of any description, and situate within the boundaries so defined, the sum of twenty pounds. 3. Such sum as aforesaid shall be paid on demand to” – Ref. NZLII

“Sustainable organic production, zero carbon footprint, 100% biodegradable, mortgage free, locally produced, solar heated, earthquake-resilient, reduces unemployment, zero toxic materials, great ventilation. resistant to water damage, energy efficient, suitable for off-grid living, fully customisable, tiny home options, minimizes waste production, traditional heritage design, decreases homelessness, no subsidies required, no housing corporation or loans required, supports community autonomy. easy access to major transport routes, no expensive insurance premiums or EQC levy to pay..” – Andy Wonder, comment to AHNZ (2024)

Humans have been living in fiber houses since antiquity and the danger, especially with raupo in concentrated proximity, is the inflammability. In hot, dry, windy conditions among people who used candles or even rushlights by night there was a big risk to manage. Harman (2014) reports on Wellington’s first big fire on 9 November 1842 taking out 60-odd dwellings, half of them raupo. To stop the fire spreading people tore down the raupo and carried it by hand to the sea: Something you cannot do with wooden buildings. The fire gave occasion to re-build, quite quickly too, and more substantially and this time using slate and shingle roofing. So, Heraclitus was right as usual: fire begins and renews everything.

This shows that the government and its taxation was never required to manipulate New Zealanders into upgrading their housing technology. We could, and did, adapt to our natural and economic environment according to our own timetable the same way Europe had done. London, for example, burned down plenty of times without being made of raupo. The Colonial Government was trying to tax home owners into conforming to an arbitrary schedule. The Government itself, and the churches too, had built and used raupo huts in their early days but now they could afford better they started making a virtue of it.

—

Ref. Remembering Raupo Houses in Colonial New Zealand, Kristyn Harman, Journal of New Zealand Studies (2014)

Image ref. Taranaki Raupo House c.1860, William Andrews Collis, Tapuhi, Alexander Turnbull Library

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share