1847: Howick Fencibles Land

November 15, 2024

By AHNZ

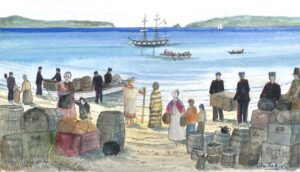

On this day, 15 November, 1847, the first Fencible families from the immigrant ship Minerva disembarked from the Government brig Victoria at Howick Beach. This being a government project, things did not proceed in an orderly fashion.

On this day, 15 November, 1847, the first Fencible families from the immigrant ship Minerva disembarked from the Government brig Victoria at Howick Beach. This being a government project, things did not proceed in an orderly fashion.

Howick was the largest of the Fencible settlements, all made up of ex-soldiers still on call should trouble break out. The site of Howick commanded one of the approaches to Auckland and was considered to be of strategic military importance.

Curious to think of the life of a life an old soldier would have led leading up to 1847. They weren’t old enough to have been canon fodder for Napoleon and Wellington. Still, they would have been very institutionalised so going from the ranks to ‘free range human’ must have been a very great culture shock.

This would be especially so because these old soldiers and their families had been horribly messed around by the government of their newly adopted country. This was the time of Governor George Grey and they would be bonded to their new home: the Crown Colony of New Ulster. Perhaps they might immigrate to the other main colony of New Munster which was intended to have its own representative parliament however 2 things stood in the way of such citizenship. Firstly, the calling of being a Fencible was supposed to last 7 years during which they had to muster on every Sunday. That sort of indenturement would drive me crazy, akin to being stuck in jail. Stuck with a bunch of other middle-aged “broken-down old soldiers” and the women and children anchored to them. Secondly, Grey never did allow New Munster to get off the ground but instead subsumed it under his own Crown Colony. The State was growing.

This would be especially so because these old soldiers and their families had been horribly messed around by the government of their newly adopted country. This was the time of Governor George Grey and they would be bonded to their new home: the Crown Colony of New Ulster. Perhaps they might immigrate to the other main colony of New Munster which was intended to have its own representative parliament however 2 things stood in the way of such citizenship. Firstly, the calling of being a Fencible was supposed to last 7 years during which they had to muster on every Sunday. That sort of indenturement would drive me crazy, akin to being stuck in jail. Stuck with a bunch of other middle-aged “broken-down old soldiers” and the women and children anchored to them. Secondly, Grey never did allow New Munster to get off the ground but instead subsumed it under his own Crown Colony. The State was growing.

“On disembarkment they would receive an advance of three months pension together with an additional one month’s pension for each child. They were to receive a cottage of two rooms with one acre of land. The men were required to attend military exercise on twelve days in each year, and on every Sunday attend muster under arms at church parade. They were also required to keep their cottages in good repair. After seven years service the cottage and allotment of land became the absolute property of the pensioner, providing he had fulfilled his conditions of service, and no further military duty was required.” – Lesley’s Family Tree

“Royal New Zealand Fencibles were brought in to garrison the area south of Auckland. These men, over half of whom were born in Ireland, were described as broken-down old soldiers. Together with wives and children, they numbered 2,581 – about 30% of Auckland’s immigrants. Another 723 men, also mostly Irish, were soldiers brought to Auckland for the war and then discharged in 1849–50.” – Encyclopedia of New Zealand (2005,) Te Ara

“8 October 1847, The Fencible ship Minerva arrives at Auckland. The destination of the Fencible families on board is not yet decided (see also 18 October 1847) and they have to remain on the ship for several weeks” – Manukau’s Journey

“two temporary 100 foot long sheds, one for women and children and another, well separated, for men….James White called it “an apology for a pig sty” as gaps were filled with bundles of tea tree or raupo… They were told in Britain that a two-roomed wooden cottage would be ready for them plus a quarter of their acre allotments cleared ready for planting. Nothing was ready for them!” – The First Fencibles arrived in 1847, Alan La Roche, Times (2018)

“‘The very first houses of many pioneer families were often raupo huts – little thatched affairs with an earth floor – very dark and cramped and highly inflammable. In country districts, slab huts

were often used until it was possible to build a more permanent frame house of sawn timber.’” – Daily Southern Cross, Auckland Museum (2023)“The idea of these men sitting quietly down in their village in the wilderness and cultivating their gardens with either satisfaction or advantage to themselves, is so utterly absurd, as to be unworthy of refutation.” – Daily Southern Cross, 6 Nov 1847; ibid

This poor first intake had been stewing since 8 October when Minerva had made port. I’m sure they wanted nothing more than to get off the ship and start living on the land again but they had no place to go.

This poor first intake had been stewing since 8 October when Minerva had made port. I’m sure they wanted nothing more than to get off the ship and start living on the land again but they had no place to go.

After 10 days, on 18 October, Grey and his people finally picked out some land east of of the Tamaki River for the Fencibles. They named it after Viscount Howick, Secretary of State for the Colonies, whose sheme this was.

Yet not until almost an entire month after, 15 November, did these Fencibles finally make it to their soil. That’s government planning for you!

So this was Howick. 2 Recently assembled sheds that segregated men from their wives and children. And these relied on raw vegetation being stuffed between gaps in the planking. Not a great position for these volunteers to be in staring down 7 more years in their new and strange land.

They had been landed in the wilderness, isolated from Auckland proper, under-resourced, and quite explicitly acting as a ‘meat shield’ against potential Maori attack. They had been at sea for months then cooped up at port for weeks more. They had been left in the lurch, bottled up as if unwanted, while procrastinating politicians wondered what to do with them. Then they were shown the ‘promised land’ which turned out to be two big communal barns at the back of beyond.

Rather than wait for their promised cottages (survivors of which you can visit at Howick Historical Village) the families turned to making raupo huts and mud huts.

Here the old warriors and their families were supposed to live out their 7 years ‘retirement’ and suddenly become gardeners and farmers as if they were Jeremy Clarkson or Ruth Goodman.

As yet another government sociological experiment in community building it’s a wonder that Howick didn’t become a breeding ground for crazy people! Maybe it did and the stories just aren’t well known? Or maybe they somehow stayed sane under all this pressure by some feat of faith or discipline? You would expect that some resentful PTSD soldier or other would pick a fight with another or even go on some drunken murder spree. ‘I lived my life for The Empire and all I got was 7 years in open air prison in the middle of nowhere’ syndrome. Yet they seem to have made good and become a proud part of New Zealand’s early settler history.

Still, it must have been a very difficult Christmas in Howick 1847 and not a very Happy New Year. At least not in terms of material comfort.

—

Image ref. Alan La Roche (who can also write and curate as well as draw)

Image ref. Fencible mud hut, Howick Historical Village. AHNZ (2018)

2 thoughts on "1847: Howick Fencibles Land"

Leave a Reply

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share

Good stuff, wow, have we got it easy these days!

Moral of the story: Don’t trust your livelihood to government!