1863: Affair At Mauku

October 23, 2023

By AHNZ

Today in history, 23 October, 1863, the Waikato War became a real kinetic engagement with the Battle of Titi Farm.

Tensions had been growing for a long time and the Auckland Settlers were anxious. Insurgent Maoris had been picking off stock, murdering farmers and children, plundering farms, and threatening massacres and wholesale invasion of Auckland itself. The Colony responded by preparing for war. HMS Orpheus was part of the effort when it dramatically wrecked on the Manukau bar upon arrival in February that year. In August a recruitment office had been set up in Victoria to recruit men to be soldiers in the coming war with the promise of payment in the land they would win in battle!

George Grey had issued the Oath of Alligence to Queen Victoria on 9 June. Those Maoris who would not sign made an orderly exodus out of the colony via Great South Road taking cartloads of their possessions with them. Maori King Potatou issued his own proclamation in June or earlier summoning fighters and instructing them on proper looting etiquette. On 12 July General Duncan Cameron’s troops crossed Auckland’s southern frontier at Mangatawhiri Stream to join the war. On 17 July, armed only with a walking stick, Cameron personally led a force to engage and expel a small Maori garrison to control the heights above the Waikato River at Koheroa. However, the first 3 months of this Waikato Campaign were uneventful. The anxious settlers had started to mock the slow pace of Cameron’s army as the troop swell continued until he could protect Auckland AND strike the next Waikato fort, Meremere (31 October.)

For those sick of waiting for some decisive action and engagement the time had come as Maori militants attacked Mauku village. In the end 8 defenders were killed and an estimated 20-30 insurgents.

“All good things must come to an end. Village gossip, in the end, shifted again from business to politics….The signs keep on coming that the now-empowered natives did not want to be part of the Crown Colony of New Zealand that had nurtured them..Morgan and his family was evicted and land confiscations followed- the Mission was no more. What Morgan had created was now used to threaten Auckland and the New Zealand Settlers.” – 1841: Otawhao Mission, AHNZ

“Dean Pitt appears to have been responsible for the entire equipping and recruiting program which included getting the men back to Auckland and trained and moved southwards to be distributed to the various posts. These were such places as Howick, Papakura, Drury, Mauku,…” – 1863: “To Make A Cullender of the Colony”, AHNZ

“Those who remain peaceably at their own villages in Waikato..will be protected in their persons, property, and land. Those who wage war against Her Majesty, or remain in arms, threatening the lives of Her peaceable subjects, must take the consequences of their acts,”- Oath of Allegiance, 9 July, 1863; Invasion of the Waikato, AHNZ

“The Manukau Natives are selling off everything they possess in the way of pigs, horses, &c. that they may be able to leave at a moments’ notice if necessary …” and “On 11 July 1863 Mohi Te Ahiatengu and others left Pukaki and headed down the Great South Road, with their movable possessions loaded into carts and drays and, according to one account, driving as many as 50 horses with them.” – What happened at Mangere in 1863? Bruce Ringer (2010,) Auckland Libraries

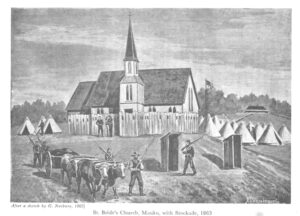

The location of the fighting was centered around the fortified St Bride’s church (image above) and the fortified tidal river landing. The battleground belonged to resident farmers John Wheeler (Titi Farm) and James Speedy (The Grange) and others. A beautiful New Zealand scene had been turned into a bloodbath.

The Merry Settlers of Mauku

Mauku country was an infertile “uninteresting” landscape of fern-hills followed by fern-flats surrounded by scrub and bush. However, from 1856 Pioneer Settlers cultivated the land and built a string of cottages and realised the colonial life every British migrant dreamed of. At Mauku the propaganda about antipodean utopia was true or made true by those with skill and a drive for hard work and determination. They had their own tidal river landing at Mauku Stream leading to Manukau Harbour and from there Auckland City and the Tasman Sea. In 1857 a post office, a general store. The Mauku Hotel. In June 1861 St Bride’s church (image, left,) Anglican, of course.

“Let him who intends writing novels about the farmer life of the colony of New Zealand take up his quarters here; let him make himself at home in the farm houses of the Mauku, so abundantly blessed with rosy daughters…. There live the Speedys, the Vickers, the Crispes, and whatever the names are of all the amiable families in that District.” wrote Ferdinand von Hochstetter in his 1858 journal while visiting the settlement.¹

This was exactly what New Zealand was supposed to be; Promise fulfilled. “There was shooting and fishing for the men, a chess club that met weekly, concerts featuring locally written plays, and a weekly dance held in turn at three of the largest houses, followed by a walk home..” They had fishing, wild food, home-grown fruit and vegetables and livestock and fairly easy river communications in and out. Mauku offered its hospitality to notable visitors of the day such as Hochstetter, Governor George Grey, Bishop George Selwyn, and William Fox. At the Speedy house they even had a pet monkey with “a taste for cake!”

“One day the Mau Mau came, All we had was lostIn our old colonial home, Under the Southern CrossLeave my monkey alone, Leave my monkey alone” – Leave My Monkey Alone, Warren Zevon (1987)“The ride is about the most uninteresting I have had in New Zealand. Fern hills are succeeded by fern flats, the land being of the worst quality. As one nears the Mauku settlement, something akin to cultivation is visible, and close to the belt of bush by which the range of vision in front is bounded, the eye is relieved to a certain extent by tho sight of several cottage residences of settlers.” – Daily Southern Cross (1863,) Papers Past

“Social life seems to have been particularly lively. Day pastimes consisted in shooting wild cattle and pigs, and the native pigeons, then very numerous. Pheasants were early introduced, and increased amazingly. The salt-water creek gave them good sea-fishing, and the streams plenty of eels, some of which reached an enormous size. They must have worked, as the results showed, but certain it is most of the stories the old hands used to recount with gusto were about their frivolities. And gay as the days seem to have been, the nights were gayer still. They had a chess club with weekly meetings, concerts, at which they acted little plays and charades, card parties, and a weekly dance, held in turn at the three largest houses. Scarcely an evening passed that there was not a gathering at some-one’s home, and to plod two or three miles home along a rough bush track by the dim religious light of a colonial lantern (a bottle with the bottom knocked out, carried upside down with a candle in its neck), was looked on as part of the game that only added to the zest of life.” – Memoirs of Sarah Speedy

“The gardens of all the settlers have now the appearance of long neglect, as have also their houses, and tho truth is the labour of years has been thrown away.” – Daily Southern Cross, ibid

Great life in the 1850s for New Zealand’s bucolic little pockets like Mauku. Government was very small. They worshiped their own way, nourished their own local culture and spoken accent. Sung their own songs, wrote their own plays, worked hard and socialised in close community. The Mauku Settlers also had excellent relations with the local Maoris who, for example, hosted a Christmas feast in 1858 for their new neighbors. It wasn’t until the 1860s that a shadow fell over these idyllic times and led to Mauku becoming Ground Zero for the horrible Waikato War.

War Comes to Mauku

War Comes to Mauku

The peaceful, productive, life came to a stop in the 1860s. Years of work developing and growing the region were put to waste because of the native threats toward their former friends. Men like Tamati Ngapora and Potatau Te Wherowhero had been pledged to be protectors and allies to New Zealand Colony but due to an internal culture change with their people they found they needed to flip-flop on their promises in order remain popular as leaders. The roots of this change seem to come from a new generation of Maoris deep in the Waikato who grew up taking the achievements and prosperity of places like Mauku and Te Awamutu for granted. These young ones didn’t know what it was like before plenty and peace so didn’t mind gambling them away for their own ego. This new generation of native started murdering, exiling, and confiscating land and didn’t stop in Te Awamutu. Through ignorance and lack of experience they thought they could threaten the British Empire and prevail. Ref. 1841: Otawhao Mission, AHNZ

Major James Speedy was a leading Mauku citizen and one who had retired from war to help create this quiet 1850s paradise. Apparently dying of consumption he turned in his army commission for a block of land to live out his final days. The idea had been to crate a family farm at Taranaki or perhaps Canterbury with his fellow shipmates on the Oriental. Somewhere I read, or was told by his descendant, that the Governor himself persuaded the Speedy family to go to Mauku in 1856. Because Oriental was much delayed in Auckland, had lost its crew to the Australian gold rush, and had been something of a nightmare voyage, it must have seemed a better idea to get started farming right there in temperate Auckland. So, Speedy settled into country life as the Resident Magistrate and Post Master at Mauku. And, he did not die but recovered! Sadly, war was not done with him.

According to Wily (1939,) “A native woman told Major Speedy that it was the intention of her people to murder all the white settlers in Mauku in their beds.” Speedy had been written to by several others such as Chief Ahipene Kaihau, Hori Tauroa, and Waata Kukutai along the same lines (Ref. Manukau’s Journey.) Later, it was disclosed that during the July 1st “loyal celebrations” at Mauku for the wedding of future King Edward a massacre had been planned of the Settlers. However, their revels spooked the insurgents who thought they had been exposed! Also, they felt they had to abort the mass killing least the king’s daughter be captured in retaliation.

“A massacre is said to have been planned and a time chosen when it was realised that Princess Sophia, daughter of the Maori King, was visiting her relations at Mangere. It was feared by the conspirators that she might be in danger, apart from being a useful hostage if captured, so another night was chosen. This coincided with one of the settlers’ gayest celebrations — that marking the marriage of the Prince and Princess of Wales 3 – and the countryside was well lit with bonfires on all the principal hills in the district. The Maoris abandoned their plans and retired to their settlement to keep watch during the night. The settlers knew nothing of this episode until some time later when an old Maori lay-reader told Major Speedy of the danger that his family had escaped.” – Drummond (1982)

“The Maoris, it was said, were about to start out on their raid, anticipating the British declaration of war, but the unexpected glare of the bonfires alarmed them into the belief that their plans had been discovered, and that the fire was a signal for a general attack on the Kingites.” – Cowan (1955)

“By way of commemorating; the Prince of Wales’ wedding the settlers found Auckland lighted bonfires on the hills. This terrified the Maoris, who looked upon it as the signal for a rising of the Pakehas to destroy them ; and they accordingly fled to the hush, where they remained skulking for some days. This in turn alarmed the settlers at Waiuku and elsewhere, and the women and children were sent post haste into Auckland for safety.” – Who’s most afraid?, Wanganui Chronicle (July 1863,) Papers Past

“Have a read of the story behind this fortified church, the embrasures still visible on the outer walls of the building. This was built at the time of the Waikato War in the 1860s. If worst came to worst, the church was the last hope of safety for settlers caught up in the conflict if it came to their district.” – Timespanner (2008)

After this incident it was clear Mauku was in peril. St Bride’s church was fortified and shooting loopholes (still visible today, see image below) installed. The river landing treated likewise. The women and children were sent away and fighting men stationed to protect the threatened settlement.

Skirmishing Battle around St Bride’s

Skirmishing Battle around St Bride’s

The blow came in the early morning of 23 October, 1863, and the Mauku defenders were ready. However, Maori insurgents on the offensive were either more ready still or else faster at thinking on their feet. The defenders were the Forest Rangers, local Mauku man Lieutenant Daniel Lusk in command. Also, the militia of Mauku Company of Forest Rifles.

Responding to gunfire, Lt. Lusk led a force of about 20 men, including the famous Gustavus Von Tempsky, to investigate. What they discovered was that Lusk’s own house had been pillaged and cattle shot on Wheeler’s and Hill’s farms. Lusk instructed Lt. William Percival to leave 15 men to hold the lower stockade and take the rest of his militia (12) to reinforce St Bride’s.

Percival, while following these instructions, decided to go on side-quest of his own making with the 12 men. Having spotted the offending Maori warriors he took the rash initiative of trying to attack them from behind and expecting Lusk to join in. However, this left Lusk’s force and the defenders of St Bride’s wondering what the hell was going on now!? Percival had bitten off more than he could chew in an unequal fight and was being driven, bit by bit, into the open and to certain death.

Lusk and von Tempsky converged on Percival’s position and rescued them from certain doom. Somehow none had yet been killed. The Maoris they were fighting were driven off. It would have seemed like a time for relief and counting lucky stars and putting some hard questions to Percival such as “What the hell did you think you were doing?” But it was no time for dropping one’s guard. This was only the beginning.

Many more Maoris, new ones, silently and suddenly closed in on the defenders! Outflanked and out-numbered, it was now that 8 were killed. This number includes Percival himself who was apparently gripped by a berserker rage and had to be held back from charging into fire. Maybe that was his mental flaw all along that put his comrades into the trouble they were in?

“According to contemporary newspaper reports, Lieutenant Percival was actually J.S. Perceval, grandson of British Prime Minister Spencer Perceval, who was assassinated in the lobby of the House of Commons in 1812.” – Waikato Regiment NZ Wars memorial, Drury. nzhistory.govt.nz

“Lusk’s house had been pillaged…the Maori had shot a bullock. The force, hearing the shots, divided, and twenty, under Jackson, Lusk, and Von Tempsky, scouted about the fringes of the paddock, keeping under cover of the bush. They received a sudden volley at a range of a few yards, and replied briskly.” – James Cowan, Von Tempsky & The ‘Cool’ Mauku Cats (2015)

“There are some cool hands amongst those Mauku Rifles…watching the Maoris like cats; they have holes through their coats, but none through their skins as yet.” – von Tempsky, ibid

“Lieutenant Perceval set out as ordered, at the head of twelve men, but instead of following instructions to join the others at the church he struck off to the right for the crown of the Titi Hill, with the object of taking the Maoris in the rear. These rash tactics quickly involved Perceval and his small party in a perilous position from which it was necessary for Lusk to extricate them.” – Cowen (1955)

“Tho bodies of seven men were found laid out on the green sward on the crest of the hill, a polo on which a white haversack was fastened marking the spot. They were all frightfully tomahawked, and partially stripped. Lieutenant Perceval’s remains were horribly mutilated. ” – Daily Southern Cross (1863,) Papers Past

The defenders were all in a Kill Box now and had no option but to expose themselves in an effort to break away to the safety of the bush. Under fire, this they did but not without loss. The survivors made it to the safety of St Bride’s Church. The dead were mutilated by the Maori foe who seem to to have taken full heed of the Maori King’s memo about not stripping the dead of clothing. Von Tempsky, of course, would go on to make a war target of the Maori’s food settlement Rangiaohia but in a far more generous and orderly way. He would die in 1868 at the Beak of the Bird but his body was never recovered. In the 2020s von Tempsky’s memory is denigrated and the monuments raised to it are being cancelled.

Fittingly, Reverend John Morgan officiated at the funeral of the fallen. It was his Maori flock who had taken his gifts, grown strong, then exiled him and instigated the spirit of the war that would back-fire horribly.

The old fortress-church of St Bride’s still stands with its own graveyard, community rooms, and neighboring cows. I think what happened 160 years ago today is little remembered these days because it doesn’t fit the storyline of our era. It’s not Politically Correct to remember that Auckland was defended from invasion in the 1860s just as it was in the 1850s. It’s unpopular to suggest the Mauku Pioneers were hard-working decent New Zealanders who supported and defended this country and that their vision of a better life had any good points. I think this attitude will swing around back to favoring the Pioneer Spirit again in the decade to come and it is for people who feel that way that I write these posts. We’ll just have to see how many statues, memorials and street signs survive until the turning of the tide. If Wokesters knew more about New Zealand history they would probably try to Cancel St Bride’s historic church with a box of matches before anyone can work out how important it is to New Zealand’s heritage.

—

1. The Waikato Journals of Vicesimus Lush, Alison Drummond (1982,) Early New Zealand Books, Auckland University

2. Memoirs of Sarah Speedy, Allan Speedy. speedy.co.nz

Image ref. St Bride’s and the 1927 memorial, AHNZ Archives (2017)

Image ref. G. Norbury sketch of St Bride’s, 1863.

Ref. South Auckland, Henry Wily (1938,) Papers Past

Ref. The New Zealand Wars, James Cowan (1955)

3 thoughts on "1863: Affair At Mauku"

Leave a Reply

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share

A great recount of this incident. I learnt a lot from it, great researching. A few years ago, I visited St Brides on a Sunday, still in popular use by the community. I tried to find the place where the engagements and the old port was but wasn’t overly successful in that endeavour. They should put up some signage.

Your philosophical musing that the current wokesters and narrative will fade is probably correct. NZ history is well documented in books, so people will come back to these and rediscover what actually happened.

Yes, I think they will. Time comes when being ‘conservative’ becomes the new radical.

I would like to find that old port too. Good job for the canoe. Had a hard time finding that monument!

And yet revisionist historians like O’Malley state that the invasion of the Waikato by the British was unprovoked. Another provocation was the attack on the signal station flagstaff at Manukau Heads in November 1863.