1873: Softness of Brain

September 11, 2024

By AHNZ

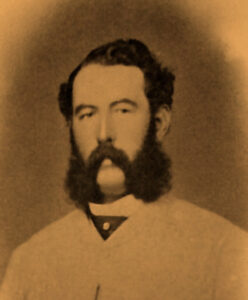

Today in history, 11 September, 1873, the father of the New Zealand Police Force died. I’ve named an era after him called Branigan Honor Culture. He was St. John Branigan and that would have been pronounced ‘Sinjin’. New Zealand’s top policeman in his day.

Today in history, 11 September, 1873, the father of the New Zealand Police Force died. I’ve named an era after him called Branigan Honor Culture. He was St. John Branigan and that would have been pronounced ‘Sinjin’. New Zealand’s top policeman in his day.

Otago’s gold diggings were attracting a great many Australians. Logically this, in turn, attracted problems of justice that came along with them. So, the Otago provincial executive kept with this chain of logic by bringing in a Victorian lawman in late August 1861. ‘Sinjin’, in charge of 19 Victorian Mounted Police. Branigan’s Troopers were responsible for the arrest of many of their fellow Australians including the infamous Maungatapu Murderers.

Branigan had been on leave from his Victorian service and now resigned and became Commissioner of Otago Police. A very powerful figure in the thick of the flow of enormous wealth coming out of the Otago diggings. “Branigan had become one of the most powerful and influential figures in Otago.” Ref. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara

His fame and might was so powerful that a goldfields town was named after him, St Johns. However, in a case of history revisionism it was to become what we know as Kingston around the time Branigen left the wild golden frontier.

In 1869 the Continuous Ministry decided to get their hands on the institutions of law enforcement. It was Branigan they called upon. As Commissioner of the Armed Constabulary he helped them nationalise the local forces and re-organise them. Our own paramilitary police. It was really a purge. “Worthless” people were removed and personnel picked by Branigan were enlisted. The Public Relations selling point was that this was “demilitarisation” and the exhausting and unstable period of the Maori Wars were over. Branigan became even more powerful. He also made a great many enemies as his new broom swept away the little fiefdoms of Colonial New Zealand.

“Branigan came to New Zealand with 20 hand-picked volunteers from the Victorian Force. With these he quickly established law and order in the mining camps and provided efficient armed escorts for gold shipments from the diggings to Dunedin. The competence and reliability of this force soon won the settlers’ confidence and approval. In 1863 Branigan was promoted to the rank of Commissioner. His general efficiency in this post made him known throughout the colony, ” – NZ Encyclopedia (1966)

“The ‘great demilitariser’ threw his boundless energy into converting the army of ‘ragged and war-worn soldiers’ into a ‘small but highly trained Force’ of disciplined police. He toured the North Island inspecting units and weeding out ‘worthless’ men, and as acting under secretary of defence he reorganised New Zealand’s internal defence system…a controversial decision. Opponents, including the Armed Constabulary’s deposed leader, Lieutenant Colonel G. S. Whitmore, ridiculed the process…would they capture Te Kooti, who still eluded all pursuers?…the reorganised constabulary would gradually take over policing in the provinces.” – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (1990)

“The General Government…sought to phase out regionalised pakeha policing in favour of the centrally controlled Armed Constabulary; in 1870 Auckland Province was to voluntarily surrender its police force to absorption by the Armed Constabulary. In 1877, after the abolition of the provincial governments, the police forces of the eight other provinces were likewise fully incorporated into the police/army Constabulary headquartered at Wellington. In 1881 the Maori King made his peace with the state and the Armed Constabulary invaded Parihaka, the last major bastion of resistance—albeit ‘passive resistance’—to land confiscation; and on 1 September 1886 the policing and military functions of state were finally organisationally separated by statute.” – Policing the colonial frontier : the theory and practice of coercive social and racial control in New Zealand, 1767-1867, Richard S. Hill (1986)

“Branigan rode out to Onehunga to meet a group of recruits for the constabulary. He fell ill with what was said to be ‘severe sunstroke’. After the spread of rumours, the government admitted that Branigan’s ‘mind was completely overthrown’…reportedly ‘as mad as a hatter’, and so in May he was committed to the Dunedin asylum under the Lunacy Act…Branigan continued to deteriorate mentally and physically, and from April 1872 was under constant and severe restraint. Eventually he was permanently bedridden and ‘had to be attended to as a child’. He died on 11 September 1873 from, in the words of coroner T. M. Hocken, ‘softening of the brain’.” – ibid

“”Kingston has not always been known as Kingston….in the early days of European settlement the township was also known by the name St Johns, after an Irish-born policeman who wielded a significant amount of power in the fledgling colonial community…The town became known as Kingston by mid-1864 to mirror its neighbour on the opposite shores of Lake Wakatipu, Queenstown.” – Information panel at Kingston, AHNZ Archives (2023)

Branigan did his job for the politicians so well that the police haven’t needed a major reform since. (However, the more Woke-Diversity police cars they make the closer we get to End Game on that…)

Arguably the most powerful man in New Zealand in his day. So, of course, he had to go. The wealthy gold town of Kingston had to be re-named as it was once named after its He-Man. One day, at the height of his powers, Branigan simply came down with a bad case of “sun stroke.” After that, he spent the rest of his life in restraints at the nut house until finally dying of “softness of brain.” Sounds legit?

Not to my cynical Anarchist mind! My opinion is that by late January, 1871, Branigan’s service had been rewarded with so much power and influence that he had himself become a rival to the ruling elite. Men like William Fox, Donald McLean, and Julius Vogel should have felt threatened by this southern hemisphere General Custer. Custer, another martial man who rose to fame, was a potential contender for the 1876 presidential election until being famously taken out of circulation by the fiasco at Little Bighorn (1876.) Branigan was taken out of circulation on an inspection ride to Onehunga. Officially it was severe sunstroke that led to 2 1/2 years of captive insanity followed by death due to ‘softening of brain.’

In November 1871 the Continuous Ministry passed the Branigan Allowance Act which was a private social welfare system fund especially for Sinjin, his wife, and the children. Parliament had evidently decided that Branigan was to never recover. But he lived almost 2 more years.

Sunstroke leading to lunacy? Or, might Branigan not have been ambushed and detained? A conspiracy could involve the Continuous Ministry itself or vengeful municipal police forces, and ex-members, who had been insulted and disenfranchised by Branigan’s reforms. Until dying of “soft brain” the old police chief was “under constant and severe restraint.” Maybe even drugged? He may have been sick although this doesn’t sound like a symptom of sunstroke ever heard of before or since. It sounds more like George Orwell’s 1984. Do you think Branigan was put in Room 101 for being a problem for Big Brother?

I would be extremely interested to know what his wife¹ and children thought and if it goes against State history. My suspicion is that they were hushed up and prevented from visiting Sinjin during his incarceration.

—

1 Wife Margaret Branigan died herself 3y later in 1876 leaving at at least 2 teenagers behind. Ref. Find A Grave

Image ref. Branigan. Otago Settlers Museum. AHNZ enhanced (2024)

Southern Heritage Trust Southern Cemeteries Tour by Gregor Campbell. Dunedin Recollect (2021)

2 thoughts on "1873: Softness of Brain"

Leave a Reply

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share

Yes, my old theory of see what happens and look for reasons, I too would like to know what the family thought although I suspect they were sweet talked.

I put in extra homework last night to find that wife Margaret died after 3 years. That’s when we got the big police grave monument for the couple. There were 2 or 3 children including Cecil (a twin?) who worked for the government, died 1946. Daughter Amy Browne (d.1943) would know the most and perhaps told the true history to daughter Amy Margaret (b.1885) who moved to London. That’s where the trail ends for now.

“I suspect they were sweet talked.”

Seems to be financial pressure as the Branigan Allowance Act (1871) LEGISLATED a pension for him in the madhouse and wife “if she survives” and the kids. Why would they even need that unless Branigan’s significant earnings/savings had not been interfered with?