1912: Spring Cleaning at Waihi

November 12, 2023

By AHNZ

Today in New Zealand history, 12 November, 1912, the mining town of Waihi was subjected to a good Spring scrubbing.

For most of the year the town had been occupied by hostile unemployed men who demanded mining jobs on their own terms. They had no other main focus but to disrupt, abuse, taunt, and even throw stones at the working people of the town. A large police presence was deployed to hold this very tense situation in check. Today the situation came to a full head of steam at last when the occupiers were ousted from their HQ followed by being driven out of the town permanently. To State History and the Left it is known as Black Tuesday.

According to Moon (2011) over a decade of “socialist rabble-rousing and indoctrination” had led up to the occupation. These militants tended to be “vehement atheists, self-conscious spokesmen for the working class and prophets of revolution.” says New Zealand’s Heritage (1971) encyclopedia. And that, “Governments, armies, navies and monarchs too, were puppets of the “master-class” of capitalists.” according to their conspiracy theories. They were out of step with mainstream New Zealand by these radical ideas and, for example, did not lower their Union Hall flag when the king died nor fly one at the coronation of the next.

Some members of the Waihi Workers Union had become disgusted, at last. They did not feel represented by the loopy Lefties who had captured their union. They didn’t want to be associated with its political ideology or local body election campaigning. Especially not when they were loyal to their king or faithful to their church and the union denigrated both. Of course, the Union was looking out for members who did share those values and neglecting many who did not. So, quite understandably, a new union formed around some 40 stationary engine drivers in May 1912. They were known by friends as the Arbitrationists because they wanted to work within existing employment law whereas the Waihi Workers Union called them “Scabs” while demanding that management force them to return to the fold of the Waihi Workers Union.

Of course Management refused this ultimatum and so the lock-out/strike began. Spokesperson for the Lefties, Robert Semple, doubled down with the same attitude of compulsion that doomed the Strikers into an impossible strategic position. He said, “You want a fight! Well, we are going to make it a bitter one, and bitter to the end. The gloves are off and it is going to be a knuckle fight.”¹

Of course Management refused this ultimatum and so the lock-out/strike began. Spokesperson for the Lefties, Robert Semple, doubled down with the same attitude of compulsion that doomed the Strikers into an impossible strategic position. He said, “You want a fight! Well, we are going to make it a bitter one, and bitter to the end. The gloves are off and it is going to be a knuckle fight.”¹

These simple, r-selected, Lefties didn’t understand Game Theory. The strategy of insisting on making the conflict into a “fight” settled by force that would go to the “bitter end” precluded the possibility of a Win-Win outcome. The Strikers were now unable to back down without dishonor and embarrassment. Yet, the only way they could win would be in a revolutionary act that would overthrow the State itself! That just wasn’t on the cards. They were deluded. Defeat and disaster was already assured in May 1913 yet the Strikers were stubbornly gripped by their total pig-headed unwillingness to look facts in the face.

Bob Semple was not this silly. He was one of the key leaders in charge of the Federation of Labour to whom the Strike’s management was handed over to. The Federation knew how to read this Conflict Table (right) and didn’t pick this fight or strategy. The Strikers started playing this game of chess all on their own, made a bad opening move, then handed over the playing to the Fed. Rather than pledge its full support to the strike or even let its leader explain it to them the Fed refused to do either! The Waihi Strikers had over-played their hand. The Red Revolution wasn’t coming. The reputations of Fed leaders Semple and Paddy Webb soared because of their ideological utterances. Great for their future careers in politics but it came at the exploitation of the Strikers who would have to deal with the real world consequences of loosing this fight. Webb and Semple would, of course, eventually become Ministers in the Labour 1.0 Government.

“It’s just 37 years since the Waihi Strike….I got to know Bob Semple and Peter Fraser well then. Those were they days when they were close to the workers. They also helped and led the workers in their struggle to a greater share of the country’s wealth and toward socialism.” – Charley Oakley, Fighting Back 1949, The Workers of Auckland, NZ Sound and Vision

“The strike was broken, their jobs were gone, and now the only safe option was to pack up and leave Waihi forever.” – Trotter

“Four of the federation’s five key leaders were Australian socialists and unionists, while others had experience on British and American coalfields” – A Concise History of New Zealand, Philippa Mein Smith (2005)

“So the version of socialism that prevailed in New Zealand prior to the First World War was never a homespun variety, as some later observers of the labour movement were inclined to mythologize. Rather, it was aroused by activists and agitators who travelled throughout the Pacific Rim in the early decades of the twentieth century, disseminating radical ideas about reform and even revolution to the working classes — those ‘most likely to be infected with socialist ideas’, as one historian put it.” – Moon (2011)

Interesting to note that these political careerists were not workers themselves nor even New Zealanders. Usually Australians, they came to our workplaces to make a living out of sewing resentment and promising ‘social justice’ to the gullible.

Waihi Occupation Ended

From May to November, 1912, the Strikers simply occupied Waihi. Having no work they relied upon welfare sent to them from other unionists around New Zealand and Australia. This allowed the Occupiers to be full-time provocateurs looking for a fight. They taunted and threw stones at the workers. According to Moon (2011) some of thing things the Arbitrationists were called were horrible end even racist. “Hired thugs,” “toughs,” seasoned criminals, “bruisers,” “Maori half-breeds and tribal outcasts.” Waihi became a powder keg of tension and volatility. The Strikers occupied their Miners and Workers Union Hall 24-7 like a fortress.

Police Commissioner John Cullen placed a cordon around the town to prevent more provocateurs from entering. After all, there was a free living to be had paid for by Federation of Labour affiliates working elsewhere. If you did not want to work but wanted to be paid as a professional Left-Wing activist then Waihi was the place to be. The Strikers should have welcomed more sponsored Socialist ideologues to their local cause to help throw the rocks and the insults no matter if such useful idiots would work or mine in the event that they ever won the jobs back.

On 10 June, 1912, New Zealand’s political scene was shaken as William Massey won the General Election and formed a Ministry. This was the first time since 1890 we were not being governed by the Lefty Liberal Government; It was the end of an era. Needing to make his mark, Massey wasn’t going to go soft on the Occupiers. For them to have succeeded in their tactics would have risked a domino effect all over the industry and labour market. Massey had a big job to do in taking back political and social control of the country. As Waihi was demonstrating, the old Conformity was not simply willing to surrender their hegemony peacefully. Ref. 1912: The Death of the Liberal Party, AHNZ

From November 9th things got hot as fights erupted in Waihi between the Occupiers/Federationists/Strikers and the Arbitrationist factions. The Strikers evidently fled to their Miners’ Hall as refuge to rest and recharge then emerge to resume more spot fights. The New Zealand Herald reported that the Hall was stormed more than once. Commissioner Cullen once more intervened, and “vigorously forcing his way through the crowd, succeeded in mounting the steps leading to the door of the hall. In decisive tones he ordered the workers to desist. Somewhat reluctantly they obeyed and turned their attention to any other federationist who ventured forth into the street.” Ref. NZH (1912,) Bromby (1985)

It would be strange for the Occupiers to admit that the Police protected them this way. They believed, after all, that policemen were puppets of a Capitalist Master Class. If they were protecting Striker’s rights to protest and Occupy, and defending their Hall too, well that must be some kind of long game on the part of the Masters? And, if the police were not neutral but picked a side, why did it take so many months to break the Occupation? Did the Strikers really think they were holding their own against both the workers and townsfolk as well as 150 armed police? It’s a conceited idea yet their narrative relies upon it.

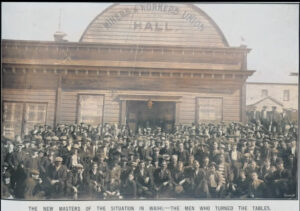

On 12 November the Miners’ Hall was stormed. This was either incited by shooting from the hall or else soon involved a shot that hit one of the Arbitrationists in the knee. This was Thomas Johnston of whom Trotter (2007) writes “Hearing his anguished screams, the milling crowd of scabs which had marched down Seddon Street shortly after sunrise became a howling mob. As the hall’s front doors gave way, Evans and his two comrades inside retreated in the direction of the rear exit.” According to Harry Holland there were 7 or 8 holding the Hall of which Fred Evans was considered responsible for the shooting. The line had been crossed now and the Occupation was set upon and evicted from Waihi entirely.

Evans was given such a beating there and then that he later died in a coma after first being arrested and taken to hospital. Johnston, on the other side, was repaid for his efforts by being taken from hospital to the Whau Lunatic Asylum in Auckland (aka Avondale Mental Asylum, AKA Oakley Hospital.) Apparently he had had a bad reaction to the anesthetic. Despite a clean bill of mental health he discharged himself and limped his own way back to Waihi and his family much the worse off for his involvement in the day of infamy.

“Johnston considered himself to have suffered as much abuse at the hands of the strikers as anyone, and when the opportunity came for revenge he was in the vanguard of the strike-breakers’ attack. On 12 November he was at the front of a crowd which stormed the strikers’ hall. In the resulting mêlée – in which one striker, Frederick George Evans, was fatally injured – Johnston received a bullet wound to the leg.” – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (1996,) Te Ara

“Harry Holland gave an account of the clash of 12 November, which, although jaundiced, still gives a sense of the episode: ‘The police and police-organised toughs having smashed into the Miners’ Hall, without warrant and without reason, the seven or eight men and women inside fled for their lives …. On the head of Frederick George Evans — described by the police themselves as quiet, unassuming, and undemonstrative — the central force of that drunken fury of death and of unloosened hell happened to fall.” – Moon (2011)

“As the day wore on, the scabs moved from one striking miner’s house to the next, informing them in graphic terms what they could expect if they remained in Waihi…the only safe option was to pack up and leave Waihi forever. Michael Rudd, leader of the ‘company union’ whose members now occupied the union hall, had drawn up a list of the families to be expelled from Waihi…This was political cleansing, undertaken and overseen by New Zealand’s chief law enforcement officer, at the behest of the dominion’s attorney general.” – Trotter (2007)

“The New Zealand of 1912 was in one of its mini-civil war time periods. The previous 20 year era had been what Strauss-Howe Generational Theory refers to as Third Turning: Unraveling. The old social order and national identity had been picked apart so that by 1912 the time had come for 20 years of The Fourth Turning: Crisis.” – 1913: The Great Strike Boogaloo, AHNZ

Waihi was now subjected to a Political Cleansing as the Occupiers, including their wives and families, were forced out of Waihi forever. Their Live Action Role Playing at a Socialist Revolution was over. That job left up to the Russians in 1917 and based on the Stalinist dictatorship it directly led to New Zealand, if not Thomas Johnston, had dodged a bullet.

It couldn’t have gone down any other way since the Occupation had insisted on this way of conflict settlement from the outset. The Federation of Labour was in a tight spot of ambiguity. On the one hand they were tied up with the Strike and their reputation would sink with it; Apart from the future Labour politicians who used the incident as a booster rocket for their careers. At the same time they did not put that famous “socialist solidarity” in behind the Waihi Strikers, did not call a General Strike even for a single day, and many of the composite unions refused publicly to support the Strikers. NZH (1971) says “Only a handful of miners’ unions proved willing to give much…the Wellington council wrote to the Sydney Labour Council advising against giving money. Also, the rival United Labour Party, which had some 60 affiliated unions, refused to support the Waihi strikers and a number of its leaders made critical remarks…the (Labour Party) clique…through their paper, with venom and hate, the strikers at Waihi and the Federation.”

For the new K-selected New Zealanders the cleaning up of Waihi was the start of their taking back New Zealand from the Liberals. The future of the country was being reset.

For the r-selected group the disaster of Waihi served to shift out the old guard Liberals so that the fresh men, Labour men, would take the place of the disgraced. In defeat this faction was now able to re-form itself by ousting the failures and come back more strongly. This they succeeded in doing a generation later so that by 1936 they were running the Government. However, it had been decided that the country to be governed was not going to be a Socialist or Communist State even though the first leaders of the Labour Ministry had that background and those established credentials.

—

1 Ref. Moon (2011)

Image ref. The new masters of the situation in Waihi – the men who turned the tables, New Zealand Graphic, Papers Past, Colour by AHNZ

Image ref. Conflict table, Singapore Institute of Purchasing and Materials Management

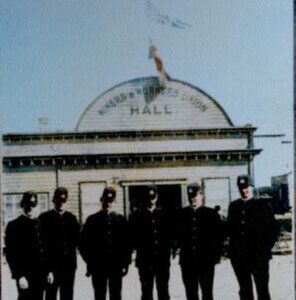

Image ref. Police patrol before the captured Miners’ Union Hall now with Union Jack and Red Ensign rather than the Federationist’s Red Flag. New Zealand Graphic (November, 1912,) Papers Past. Tuned up by AHNZ (2023)

Ref. New Zealand in the Twentieth Century, Paul Moon (2011)

Ref. p104, An Eyewitness History of New Zealand, Robin Bromby (1985)

No Left Turn, Chris Trotter (2007)

Ref. p1989, New Zealand’s Heritage (1971)

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share