1817: Tohunga Jack

April 14, 2025

By AHNZ

New Zealand, by 1867, was out of its pioneering era and into a new time period AHNZ calls the Colonial Saeculum. There was a Crisis due to the withdrawal of the Gold Rushes and Maori Wars that we had now come out on the other side of. For now we were doing well as a national economy built out of several proud and rivalrous provinces. This Provincial High (which was to stop in the following decade) provided an opportunity to look back on what our country had achieved. We had come of age enough in 1867 for the Auckland Institute and Museum to be founded.

New Zealand, by 1867, was out of its pioneering era and into a new time period AHNZ calls the Colonial Saeculum. There was a Crisis due to the withdrawal of the Gold Rushes and Maori Wars that we had now come out on the other side of. For now we were doing well as a national economy built out of several proud and rivalrous provinces. This Provincial High (which was to stop in the following decade) provided an opportunity to look back on what our country had achieved. We had come of age enough in 1867 for the Auckland Institute and Museum to be founded.

Thomas Gillies founded the Institute which we now know as Auckland War Memorial Museum with other learned gentlemen. As a top judge and Superintendent of Auckland Province it was a simple matter for Gillies to secure some land and donate a generous start-up endowment. He also served as President 3 times. These Settler and Provincial Generations wished to reach back into New Zealand’s deeper past by contacting the old timers still alive to get them on record. The Institute had already corresponded with and recruited Frederic Manning of the Hokianga who had arrived in 1833 to live among the Maoris. Gillies knew of another “Pakeha-Maori” of even earlier vintage, also of the Hokianga country.

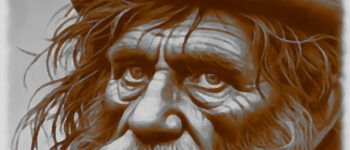

John Marmon was the prize sought by Gillies. John, or Jacky Marmon, or several other names besides, had incorporated himself with Kerikeri tribesmen in 1817. After a very eventful life the weather-beaten old man, born 1798, now lived alone up-river at Rawhia as one of the largest landholders on the Hokianga. Not that he did much with it. In the past he had been everything from a subsistence beachcomber to a hotelier with a protected trade monopoly over the entire district and a Maori Wizard besides. Now elderly, he had about broken even in life.

Gillies commissioned a scholar local to the Hokianga, Mrs Alice Bennett, to approach old Marmon to take down his story. He had become a funny old man who wore a blanket instead of trousers and a hat he made himself which was partly a top hat and partly a document briefcase. More, Marmon had a reputation as an old convict, the bogeyman to Hokianga’s children, and a cannibal by dietary pattern. It was a reputation Jacky had earned; He was all 3 of those things. Mrs Bennett must have shown some pluck or even some Joseph Conrad Heart-of-Darkness grit in venturing up river to the magic man’s lair or in having him come to her. The results were interpreted, perhaps corrupted, and published in the newspapers. In theory Auckland Museum ought to have the original Bennett manuscripts somewhere on a shelf.

“Marmon also knew, advised and interpreted for many of the first shipbuilders, missionaries, settlers and colonial locals at the Bay of Islands and at Hokianga, including Captains Clarke and Dillon, Samuel Marsden, Bishop Pompallier, Baron de Thierry, James Busby, Colonel Despard and Governor FitzRoy. One of Marmon’s most important legacies was the memoir he dictated to Mrs Bennett as a cantankerous old man.” – Cannibal Jack, Trevor Bentley (2010)

Jacky Marmon became one with the Maori tribes he joined, crossing into that culture fully immersively. He took Maori wives and issued Maori progeny. He learned the ways of Maori magic and out-gunned powerful witchdoctors, “Tohunga,” with his own powers and Western tricks such as ventriloquism. Or, sometimes, he just shot the competition in the head. That was also a solution that worked for cheating wives, his account tells us.

He worked with or knew the major players of his era and particularly aligned himself with Pompallier showing that, after all he had been through, his Irish blood still ran Catholic. For example, Chiefs Hongi Hika, Hone Heke, Muriwai, Patuone, Waka Nene. Missionaries Samuel Marsden, Thomas Kendall, John butler, Henry Williams, James Stack. James Busby tried to have Marmon arrested but his tribe wouldn’t give him up. When Governor William Hobson was trying to get his Treaty signed, Marmon resisted. When Governor Robert FitzRoy tried to take his land Marmon made a deal.

For an era in the 1830s all the movers and shakers to the Hokianga would stop by Cannibal Jack’s hotel, the largest house in the district. He had made it himself out of the kauri timber he traded in and done a commendable job. It was designed to be just like a state-of-the art Sydney pub and Marmon’s own brews were sold to the visiting traders and whalers which made him of fortune. It was so popular he even added a drinking tavern on the water on the end of his own wharf. This one could be accessed at low tide via a trap door through the floor leading directly from visiting ship to Jack’s bar. Kororareka was painted as ‘Hellhole of the Pacific’ by the outsiders seeking to make a new order in their own image; Missionaries and ‘statrepreners’ on the make wielding Royal warrants. To such people Jack was public enemy number one as publican of the West Coast Hellhole.

Eventually the Crown and Law prevailed, sinking Marmon’s old enterprise. His influence diminished as did his timber and booze trade. His social function as a go-between negotiator and translator for the Maori world had come to a close. Jacky and his epoch of untamed New Zealand were not respectable. In his aged years he was a relic of a bygone era that our Settler generation wanted to bury. Jack’s land and savings were taken by The State because he couldn’t afford the expensive bureaucratic exercises required to fight to keep them. Marmon died at Rawhia, Hokianga, on 3 September 1880, at the age of 81.

After years in the cold, as a recluse, Jack and his world became interesting again in the 1860s. Having spent the last 25 years or so burying the past the New Zealanders now wanted to exhume it and study it. Enough civilisation and confidence in our identity had now set in that it was culturally safe to study the times prior to systematic colonisation without feeling contaminated by it or associated with it. Thanks to this the Auckland Institute and Museum (1867) took an interest and sent Mrs Alice Bennett to interview old Cannibal Jack for his memoirs. They make valuable reading but are perhaps not well remembered during our Aotearoa New Zealand era because they reveal a little too much about the Maori world that the revisionists would prefer to have hidden. And, as much as Marmon’s Maori tribe embraced him as one of their own it’s not Politically Correct for Modern Maori to accept that judgement. It corrupts their revised ideas about what it is to be a Maori even though there must by now be 100s who trace their ancestry back to Jack.

–

Image ref. AHNZ interpretation of John Marmon likeness, (2025)

2 thoughts on "1817: Tohunga Jack"

Leave a Reply to Harvey Brunt Cancel reply

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share

AHNZ, you and Jacky would have go on really well!

Am amazing character in NZ history.

Uh, real life ‘Dances With Wolves’ is a bit hard core for my sensibilities. Wiping out ‘enemy’ tribes, sucking out their eyes, porting human meat up the beach…I can’t get behind that!