1861: The Invasion of Otago

March 21, 2024

By AHNZ

Gabriel Read was done with gold in March 1861 but it wasn’t to be for the first or last time. Now aged 36, Reed made his way in March to Cust in North Canterbury for the farm hospitality of his 21yo cousin, Terry Murphy. The family connection between these Australian men was that Read’s sister had married Murphy’s uncle. Ref. Edith Murphy, People Australia

Gabriel Read was done with gold in March 1861 but it wasn’t to be for the first or last time. Now aged 36, Reed made his way in March to Cust in North Canterbury for the farm hospitality of his 21yo cousin, Terry Murphy. The family connection between these Australian men was that Read’s sister had married Murphy’s uncle. Ref. Edith Murphy, People Australia

Read was afflicted with manic-depressive disorder which in the 2020s we call bipolar disorder. When elderly, this condition would be the death of him as he spent his final years an inmate of a Hospital for the Insane. Ref. Dictionary of New Zealand, Te Ara

Murphy owned his run but “continued to live in Australia, but during the eighteen-fifties he made an occasional visit to inspect the property, as did

many of his friends who were passing through.”¹ So, Murphy and Reed were probably not at the homestead, Tara, at the same time. However, Murphy was in New Zealand in July 1872 when he died young, becoming the first inmate in the cemetery he had himself donated the land for. Ref. Hunting Kiwis (c.2010)

Gabriel, like Murphy, was independently wealthy but had a “restless disposition.” At age 26 he sailed like so many young men to the Californian goldfields but the difference is that the sailed his own schooner². Read also visited the Victorian goldfields but turned away from them for the same reason as California which is supposedly the “lawlessness and violence.” While I’m sure Read probably was adverse to conflict I also suspect the depressive part of his disorder must have kicked in and made him bored and restless to travel on. But, then, the manic part would spur the man to nip off to a new and novel pursuit. And that’s what took Gabriel Read in the first place to Otago in 1861.

By the time Read arrived in Dunedin in February 1861 the reports of the gold findings were not encouraging so he prematurely terminated his first prospecting expedition, heading north to Murphy’s Run. Then, in April, new of the Lindis fold finds reached Canterbury and Read was off again! The mania was apparently back although he couldn’t have been settled down at Tara for more than a few weeks.

This time, Read did get out into central Otago around Tuapeka and on 23 May, 1861, he was the man to make the great find that started the Otago Gold Rush. Read wrote a letter to Otago Superintendent John Richardson which was duly published in the Otago Witness of 8 June. “Sir — I take the liberty of troubling you with a short report on the result of a gold prospecting tour which I commenced about a fortnight since, and which occupied me about ten days….” Ref. Otago Witness, Papers Past

“Discouraged by reports of the Mataura find, however, Read prematurely terminated his first prospecting expedition in Otago. On 11 March 1861 he left for Canterbury to visit the property of his cousin John Terry Murphy, at Cust. The Lindis discovery in April 1861 brought Read back to Otago.” – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara

“Gabriel was well educated, and when at a comparatively early age he began the globe-trotting that was to take him halfway round the world, he was already a man of property in his own right. At the age of 26 he sailed for the Californian goldfields in his own schooner. He made little money but learnt much about gold fossicking, and when he returned to Australia he became caught up in the Victorian gold rushes, mainly because Edward Hargreaves, who had made the first discoveries there, showed that the rocks and strata in the Victorian fold areas were much the same as those he had encountered in California. Read, however, did not stay long on the Victorian goldfields. The violence at the Eureka Stockade and the general atmosphere of licence and lawlessness which had discouraged him in America disgusted him in his own country. He went back to Tasmania, but he was not to remain on the sideline for long. News of gold strikes in Southland around Mataura trickled through to Hobart Town, and in the new year of 1861 he was off on his travels again.” – New Zealand Encylopedia, McLintock (1966)

“Facts indicating insanity…That he collects old gloves for which he states that he gave 1 penny per pair in New Norfolk. …has done his blanket up into a roll which he throws up to the window of his cell in order to pass the time he says. That while listening to a band playing at Bellevue Regatta he performed a kind of dance before the people and myself. That he states that boiled turnips are good for sore heads. That pickled fowls were good for any ailment. That when eating he will bite the pannikin. That he destroys his bedding and says that the cell wall is a racket wall.” – Files relating to the Administration of Intestate Estates, Tasmanian State Library

“Between 1780 and 1840 Scotland had been transformed from an agrarian, pre-industrial into an urban-industrial society. Even the Scottish Highlands were being dragged into the new industrial-capitalist economy where cash replaced kin as the basis of social and economic organisation..Captain William Cargill, were neither Highlanders nor impoverished. Like Wakefield they regretted the destruction of the agrarian and pre-industrial world and wanted to recreate the lost world of their youths elsewhere.” – Olssen (1984)

Otago Colony had been in Crisis ever since it was founded in 1848 a Presbyterian Utopia by Elderly leaders trying to re-create their lost Scotland. William Cargill (d.1860) and Thomas Burns (d. 1870) both died in their 75th year having successfully transplanted fellow Scottish Calvinists away from the over-populated, urbanising, slummy, industrial, rural poverty, and ‘spiritually corrupted’ homeland. The Scottish Pilgrims had seen off the “hordes of loose characters” who were there before them and who came to Otago since so that by 1852 the session minutes of one of their courts “reported with an air of satisfaction that “most of them had removed themselves.”” Ref. p63 Fischer (2012)

The Crisis was that Otago, in order to survive, would need to find a new identity unless it was to follow the pattern of the Amish and freeze in culture and technology. The old guard were dying off and the new adult generation simply couldn’t relate to or appreciate the late 1700s Scottish nation that existed in Cargill’s and Burns’ memories that Otago was supposed to transplant, re-create, and preserve. But if it wasn’t going to be that any more what would it be?

The Crisis was that Otago, in order to survive, would need to find a new identity unless it was to follow the pattern of the Amish and freeze in culture and technology. The old guard were dying off and the new adult generation simply couldn’t relate to or appreciate the late 1700s Scottish nation that existed in Cargill’s and Burns’ memories that Otago was supposed to transplant, re-create, and preserve. But if it wasn’t going to be that any more what would it be?

Read’s letter printed on 8 June 1861 answered that question. It was the Crystallising Moment that changed Otago and, with it, New Zealand too. Everybody was transformed by this new locus and economic basis for the society: gold.

Karl Mannheim wrote about what it means to be part of a group: “We belong to a group not only because we are born into it, not merely because we profess to belong to it, nor finally because we give it our loyalty and allegiance, but primarily because we see the world and certain things in the world the way it does (i.e. in terms of the meanings of the group in question). In every concept, in every concrete meaning, there is contained a crystallization of the experiences of a certain group. When someone says “kingdom”, he is using the term in the sense in which it has meaning for a certain group. Another for whom the kingdom is only an organization, as for instance an administrative organization such as is involved in a postal system, is not participating in those collective actions of the group in which the former meaning is taken for granted. In every concept, however, there is not only a fixation of individuals with reference to a definite group of a certain kind and its action, but every source from which we derive meaning and interpretation acts also as a stabilizing factor on the possibilities of experiencing and knowing objects with reference to the central goal of action which directs us.” Ref. Ideology and Utopia (1929)

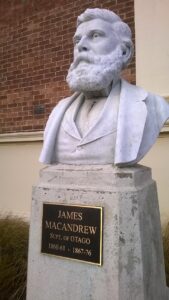

James Macandrew succeeded Cargill as Leader and did so with a very different ethic. Razzle-dazzle, spectacular public works, metaled roads and railways, industrialisation, gross imprudence. Gabriel Read had not come to dash the ambitions of Otago Provincial Councillors like Macandrew, John Richardson, William Baldwin, and John Hardy but to fulfill them by direct request. These Heroes egged Read on had the Council incentivise the hunt for gold with £500 that later became £1000 in Read’s pocket.

James Macandrew succeeded Cargill as Leader and did so with a very different ethic. Razzle-dazzle, spectacular public works, metaled roads and railways, industrialisation, gross imprudence. Gabriel Read had not come to dash the ambitions of Otago Provincial Councillors like Macandrew, John Richardson, William Baldwin, and John Hardy but to fulfill them by direct request. These Heroes egged Read on had the Council incentivise the hunt for gold with £500 that later became £1000 in Read’s pocket.

The Celtic Puritan gatekeepers of the “Old Identity” were riled but they had decisively lost the moral initiative. The puritanical and anguished ones didn’t even allow themselves to sing hymns and use a church organ so were not match for travelling musician Charles Thatcher who was the eras equivalent of a rock-star. According to one of his tailor-made songs, “The old Otago settlers, That came here long ago, Are distinguished for their being, So very dull and slow.” Ref. Olssen (1984)

Cargill’s son urged the old settlers to preserve their ‘old identity’ but the spectacular invasion was on. “It is no use fighting against fate” said the Otago Witness, “greatness is forced upon us, and we must adapt ourselves to the times.” The spiritual project was substituted for a temporal one; Otago got rich. Wasteland was cultivated, infrastructure built. Dunedin became New Zealand’s first industrialised city. Like it or not, even Cargill Jr made so much money he was able to build a castle for his family home: Cargill’s Castle.

Otago experience rapid population growth due to the invasion Reed’s find had attracted, especially from Australia, North America, and the rest of new Zealand. The Old Identity population of Dunedin town, 12,000, was replaced by Dunedin City with a population of 60,000 just 10 years later making it the largest in the country. The Rush was New Zealand’s first major burst of immigration bringing in some 200,000 people and under their own steam.

New Zealand was off on its way now! The manic-depressive Tasmanian, Read, had pointed the way.

—

1 Ref. p154, Beyond the Waimakariri, Don Hawkins (1957)

2 New Zealand Encylopedia, McLintock (1966)

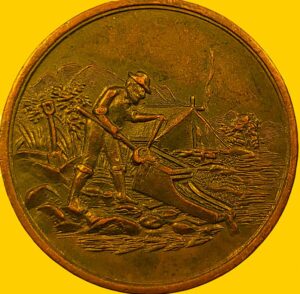

Image ref. 50th jubilee medal remembering the Gabriel’s Gully rush, Otago Settlers Museum

Image ref. Gabriel Read, A History of Gold Mining in New Zealand, Salmon (1963)

Image ref. James Macandrew, AHNZ Archive (2018)

Ref. Fairness and Freedom, David Fischer (2012)

Ref. A History of Otago, Erik Olssen (1984)

2 thoughts on "1861: The Invasion of Otago"

Leave a Reply

Like Comment Share

Like Comment Share

The Crisis was that Otago, in order to survive, would need to find a new identity unless it was to follow the pattern of the Amish and freeze in culture and technology. The old guard were dying off and the new adult generation simply couldn’t relate to or appreciate the late 1700s Scottish nation that existed in Cargill’s and Burns’ memories that Otago was supposed to transplant, re-create, and preserve

…

THAT old movie, but it is still the best movie in town.

All the social movements seem to be seeking the same thing: the perfected version of social life in our Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation.

That’s what Wakefield was trying to do too with price controls. Or Muldoon with Fortress New Zealand. I don’t think New Zealanders are aware that this is a major theme of our movie.